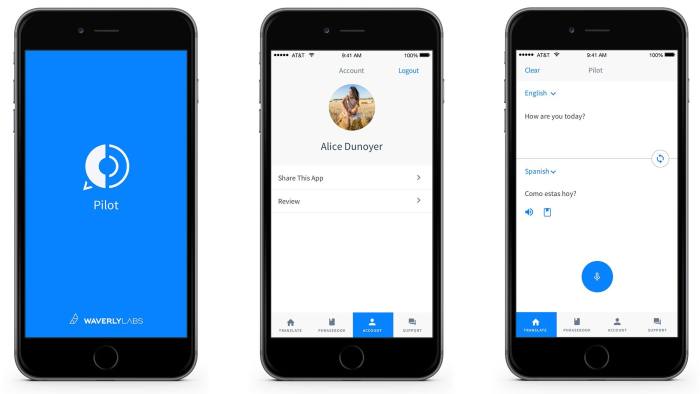

The Pilot pairs with a smartphone app to process conversations in real time.

The Pilot translation kit comes from Waverly Labs and will be available from May.

Language Tool That Can Make You a Citizen of the World

The Pilot earpiece promises instant audio translation.

by Johnathan Margolia

February 6, 2017

The smartphone equivalent of Fashion Week, the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, is looming. The star of this year’s show may not be a mobile device but a wearable accessory priced at $299.It promises to boldly go where no gadget has gone before — translating foreign languages simultaneously, like the universal translator in Star Trek, or the babel fish in the Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy.

The device is called Pilot and comes not from Samsung or Google but Waverly Labs — a New York start-up founded by Andrew Ochoa, a Mexican-American from Dallas.

On sale from May, it works like this: you, with a Pilot in your ear, speak in French, Italian, Portuguese or Spanish. I, with my Pilot inserted, hear you in English. When I reply in English, our Pilots will turn my speech into your language.

Others will be able to join us in their native tongue. A group of people, none of whom speak one another’s languages, will be able to have a conversation.

Pilot has generated more excitement than any new product I recall this decade. When I was pursuing Mr Ochoa for a meeting to talk about Pilot in New York in 2015, I got into the habit of phoning him every day for two weeks. I did not get a response. Other journalists desperately seeking Waverly Labs began to wonder if the product existed. Its unveiling is scheduled for February 27 in Barcelona, so one can only assume that it does.

When I finally got to see Mr Ochoa at Waverly’s Brooklyn office last year, he apologised for his elusiveness, saying that as many as 400 media outlets chase him at any one time.

Frustratingly, I did not actually get to try or even see the product.

Mr Ochoa, a 34-year-old business graduate who has raised $4.4m of crowdfunding for the project, said it was not ready to demonstrate. But I learnt more.

My main interest was in how Pilot works. I could not believe all the processing for multiple languages will occur in one hearing aid — sized device, and indeed, it turns out Pilots will function wirelessly through a phone app. The app, in turn, will send most of the computing work to be done remotely — in the cloud.

Pilot appears to work much like other language utilities, such as Google Translate. I believe these start with simple vocabulary and grammar rules — x is the word for y, and so on. Then they trawl billions of documents to learn the all-important exceptions to rules, or colloquial usages.

It takes time to iron out linguistic bumps. The first iteration of Pilot will be a little cumbersome. Put on hold babel-busting dreams of skipping around foreign cities conversing with the locals. Using it abroad will only be possible by burning a fortune in data charges at several dollars a megabyte. You will also need to insert a Pilot into the ear of everyone you meet.

Forget also being able to chat away with a stranger on a plane, where there is no mobile data. That will not happen for a long time.

The Pilot phone app will accompany the earpiece.

The early Pilots will, Mr Ochoa says, suffer from a second or so of processing delay and will not go beyond English and the ‘easy’ Latin languages. Mandarin, Russian, Arabic and even German will be harder to achieve and Waverly is not considering them yet.

Context is also going to be a problem. “Take the word ‘bank’, for example,” Mr Ochoa said during our conversation.

“If you say ‘I rowed my boat up to a river bank’, you don’t want the other person to hear, ‘I rowed my boat up to a river financial institution.’ But this is a technology which will get better the more people that use it.”

This is a general drawback with machine translation, which does not stop the likes of Google Translate being jolly useful and better than nothing.

Waverly’s priority, not always the most lucrative in technology, is to be first with a product like this. “The impetus to be first is powerful,” Mr Ochoa admits. “Even if it’s imperfect, it’s still pretty cool.”

“When we started, we wanted to solve a global challenge, to do something incredible. And because we came from different backgrounds with different languages, we decided language was the incredible thing we wanted to do.”

The babel fish, from 2005 film ‘The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy’

You have to admire that kind of drive towards innovation for its own sake. And I intend to be among the first to buy and use Pilot, even if it is not, frankly, brilliant. To me, Star Trek-style translation is one of technology’s holy grails.

Optimists like me who focus what new types of tech can do rather than what they cannot will love Pilot. Others less tolerant of clunky new hardware will disparage and mock it.

But while I am sure that Pilot and its successors will be hugely helpful for users from tourists to business travellers to non-profit personnel working in disaster zones, I urge caution.

Language is horrendously complex and subtle, and translating beyond most basic form — handy as it is — will be a challenge too far for any artificial intelligence we have now, or possibly ever will have.

Compared with translating with accuracy things like nuance, context and emotional intelligence, AI tasks such as guiding autonomous cars are a breeze.

![]()